Some people like baseball. Some people love baseball. Toni Stone loved baseball with a deep and abiding passion that lasted all her life, and she overcame massive obstacles for many years to play the game she loved.

Marcenia Lyle Stone moved to Saint Paul, Minnesota, from West Virginia at age 10. Her parents Boykin and Willa Maynard Stone brought their four children to the Midwest in 1931, part of a massive movement of African Americans from the south later called the Great Migration. They went to join family already in St. Paul and started a barbershop, where Boykin could use the skills he had learned at Tuskegee Institute.

Marcenia Stone became enamored of baseball as a young girl. Her parents disapproved of such an unladylike activity; her nickname “Tomboy” embarrassed them. But she was helped by her priest, Father Charles Keefe at St. Peter Claver, who got her a spot in the Catholic boys’ baseball league. It didn’t hurt that she was an excellent player. This was the first of Stone’s many firsts: she was the first girl to play in that league. After playing there four years, she said, “I knew I wanted to be an athlete. I didn’t concern myself that there weren’t any women in the game.” She told herself, “One day this is going to be my game.”

While her attendance at school was spotty at best, Stone studied books about baseball, including the rule book, and learned by watching games and practices. She also hung out around Saint Paul Saints Manager Gabby Street’s baseball school for (white) boys. She pestered him until he let her participate, telling her to “go out on the field and show those boys up.” He later said he just couldn’t get rid of her until he gave her a chance. Her ability so impressed Street that he gave her baseball shoes on her fifteenth birthday.

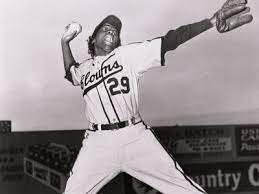

Stone also liked to find pickup games around town, and once when she asked to shag balls at a batting practice, the man who said yes was George White, manager of the Twin Cities Colored Giants. After observing her abilities he asked her to join the Giants, a barnstorming team. Playing on weekends with this team was her first big break into baseball—and she was just 16 years old. She pitched and played second base for the Giants in their games all around the Midwest and Canada.

Jimmy Lee, a local ballplayer, legendary referee and sportswriter, wrote about Stone in the Minneapolis Spokesman on July 30, 1937: “The [Colored Giants] team has the distinction of having a girl pitcher on its roster. No other team in the Northwest can boast the same. Miss Marcenia Stone, 16-year-old girl athlete, has been doing much to amuse the fans with her great catching and wonder hitting power.”

After her summer of barnstorming, Stone attended Mechanic Arts High School in Saint Paul but dropped out before graduating. She continued to play ball wherever and whenever she could, meanwhile supporting herself with odd jobs.

In 1943 Stone moved to San Francisco to join her sister Bernous, known as Bunny, who was in the army; Bunny’s marriage was rocky and she needed some family support. Marcenia traveled with very little money and didn’t even know where her sister was, yet the resourceful young woman found a job and a place to stay before she found her sister in a chance encounter.

As the “new girl in town,” Stone changed her first name to Toni, which she felt was a better fit than Marcenia. Toni was drawn to the Fillmore area of San Francisco, which some called the “Harlem of the West,” including Jack’s Tavern run by Al Love and Lena Murrell. It was at Jack’s that she met her future husband Aurelious Pescia Alberga and reconnected with baseball. Love and Alberga helped get her a spot on the local American Legion team. But to be eligible for the team, she had to be under 18, so she took 10 years off her age and said she was 16. During her career, she never corrected this bit of misinformation, likely to improve her chances of getting to play. There wasn’t much Toni Stone wouldn’t do to get to play baseball.

Jackie Robinson integrated baseball’s major leagues in 1947. This was the beginning of the end for Negro League Baseball, and team owners worried about declining revenues. Toni approached one of the owners of the San Francisco Sea Lions, one of two teams left from the defunct West Coast Negro League. She assured him she was could play as well as the men and suggested having a woman on the team might draw more people to the games. Thus in 1949 she became the Sea Lions’ second baseman.

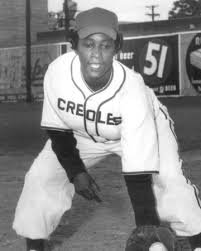

Her time with the Sea Lions was relatively brief. She joined the New Orleans Creoles, a Negro Minor League team, later in 1949. The Creoles finished first in their league that season; Toni Stone achieved a .326 batting average and played 78 games. She returned to the Creoles the following season.

Then, in 1950, she married Aurelious Aberga on December 23. As her new husband suggested, she did not play baseball in the 1951 season. His reasons are unclear, but Toni’s family thought it was at least in part because, at age 67, he needed her help repairing his home. Whatever the situation, it was a solid marriage that lasted until Alberga’s death in 1988 at age 103.

Not surprisingly, Toni Stone missed baseball. She applied to the All-American Girls Professional League (the one portrayed in the film A League of Their Own) but never heard back, because the league was whites-only. Her only real option was the Negro League, which offered her a position in 1953.

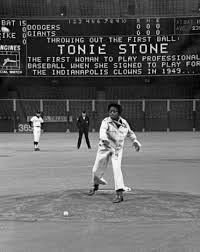

Wendy Jones says in her MNopedia article on Stone, “[She] made sports history in 1953 when she signed a seasonal contract with the Indianapolis Clowns in the Negro American League. She was hired to fill the second-baseman position vacated by Hank Aaron when he joined the Milwaukee Braves.” Any reservations on the part of her husband turned out to be irrelevant: “He would have stopped me if he could have, but he couldn’t,” Stone said, much as she dismissed her parents’ objections years earlier. Alberga soon accepted the inevitable and started supervising his wife’s daily workouts.

Syd Pollock, owner of the Indianapolis Clowns, was a gifted promoter, and he promoted Stone’s presence on the team relentlessly and creatively. He reported a greatly inflated salary, for example, and said she had graduated from Macalester College in St. Paul. Stone went along with most of his publicity requests, but stood firm on one matter: she refused to wear a short skirt like those worn in the Women’s League. She always wanted to be treated just like the rest of the players.

The team played a grueling schedule for the eight months of the season, often a game a day and two on Sundays. Toni Stone did draw the crowds, Martha Ackmann notes in her book about Stone, Curveball: “In New Orleans, Stone brought fans to their feet when she singled in a run and later started a double play that squelched a Kansas City rally. With every game, the crowds grew larger and Toni attracted more press attention.” In the team’s home opener, the Monarchs hoped for 14,000 fans in the 17,000-seat stadium; over 20,000 showed up, and Toni Stone was the big attraction.

Press coverage of Stone ranged from ridicule by the Pittsburgh Courier’s Wendell Smith to a five-page article in Ebony magazine that freely mixed fact and fiction.

At the end of the season, Stone returned home to Oakland and Alberga, and was undecided about whether to play the next season. Eventually she signed with the Kansas City Monarchs, who offered her more pay (the Clowns had reduced their offer and were hiring two more “girls” but planned to play only one at a time). But 1954 was not a successful season for her; the team didn’t play her often and when she did play she did not do very well. Her frustration erupted into arguments with her teammates and she “lost her joy for the game,” according to Ackmann. “I got tired,” Stone said. “I got so tired.”

Toni Stone batted .364, fourth best in the league in 1953.

She did not return the next year. She returned to Oakland to care for her husband, but was miserable and depressed without her beloved game. “Not playing baseball hurt so damn bad I almost had a heart attack.” There really was no place for her, in fact, with the Negro Leagues rapidly declining, the women’s league gone and the majors still rejecting women.

However, Stone slowly adjusted and a few years later began coaching the Isabella Hard Heads, a neighborhood boys’ team. Stone continued to coach and play semi-professional ball for twenty more years, until she was in her sixties. She died in 1996 of heart failure.

Toni Stone’s Legacy

Toni Stone did gain recognition later in her life for her accomplishments in baseball. Back in Saint Paul, March 6, 1990, was named “Toni Stone Day.” Doug Grow wrote in the Star Tribune that day, “Had it not been for people involved with the Minnesota Women’s History Month Project, Stone’s career may have been forgotten altogether. But in 1986 Judy Yeager Jones and others with the history project spotted Stone’s name in the footnotes of a book titled History of Black Women in America. After making contact with Stone, the History Project convinced Fridley Public Schools to pay for a plane ticket for her to come to Minnesota. Stone spoke at the schools, telling Fridley kids that it’s not always easy to achieve goals.

“’There are people who try to make it hard,’ she said. ‘There are people who call you names. But you have to keep trying. Just keep pounding on that door till it finally opens.’”

She also visited other schools in Wayzata, Apple Valley and Roseville.

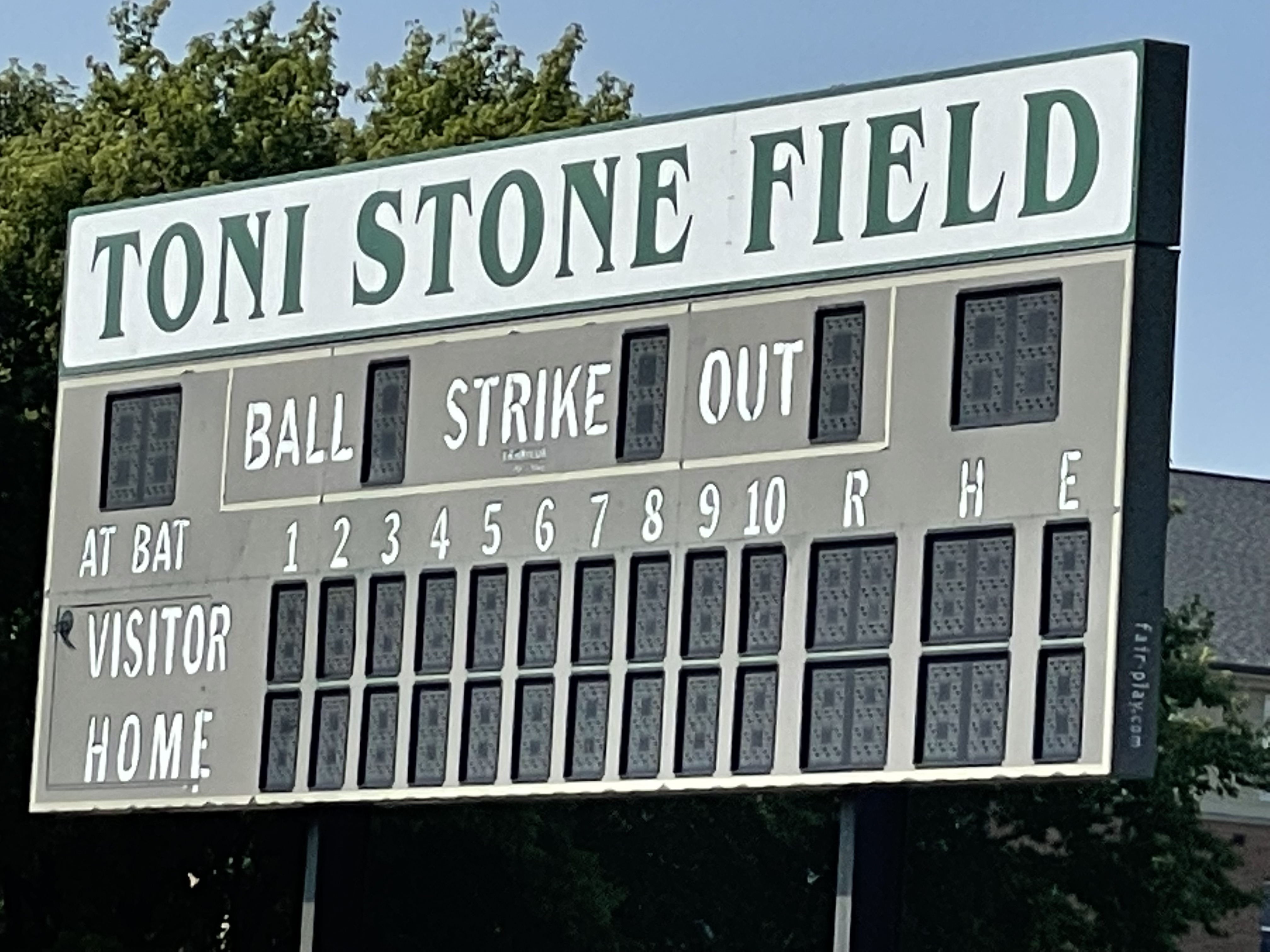

Frank White, who wrote They Played for the Love of the Game, a book about Black baseball in Minnesota, notes that the year after Toni’s death in 1996, the City of Saint Paul changed the name of Dunning Field to Toni Stone Field. Stone had played there early in her career, including when she was with the Colored Giants. Local residents held to their custom, though, and continued to call it Dunning Field, until 2012 when White “challenged the city and the Saint Paul School District to use the name Toni Stone Field on all of its schedules and other resources.” White’s campaign was successful, and a plaque was added to the site in 2013.

Toni Stone is recognized in the Negro Leagues Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, and was honored by the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1991. She was inducted into the Women’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1993. In 1997, Saint Paul’s Great American History Theater produced “Tomboy Stone.” And in 2010 Martha Ackmann’s book Curveball: The remarkable story of Toni Stone (a primary source for this story) was published. As Ackmann says in the book: “No other woman ever matched Toni Stone’s accomplishments in baseball—during her nearly two decades of play or since.”

Note: Toni Stone famously claimed she got a hit off Satchel Paige, and said it was the happiest day of her life. Stew Thornley disputes her claim in Baseball in Minnesota: she said the hit happened in Omaha on Easter 1953, but Thornley notes “the St. Louis Browns were in Texas then and did not play the Indianapolis Clowns in Omaha or anywhere else.” However, Stone’s vivid description renders the story credible. Paige was so good, apparently, that he’d ask batters where they wanted [the pitch], taunting them. Barbara Gregorich relates Stone’s version in Women at Play: “I get up there and he says, ‘Hey, T, how do you like it?’ I said, ‘It doesn’t matter. Just don’t hurt me.’ When he wound up—he had these big old feet—all you could see was his shoe. I stood there shaking, but I got a hit. Right out over second base. Happiest moment in my life.”

First published July 2023 on lisastories.com. Detailed references gladly supplied on request.

Wow; so much history that I never knew. I really appreciate you bringing the past to light.

What an amazing woman she was, not just in her era, but in ours too.

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Denise. I too found her fascinating.

LikeLike

Great article, Lisa!

LikeLike

Thanks, LeeAnn!

LikeLike

Great article! An inspiration for all.

LikeLike

Hi Lisa,

What a fascinating, determined woman with a singular and abiding love for baseball! You tell her story well. Hope you have more stories on the way.

This summer had evaporated -in many ways-and I am now getting to long neglected projects. Yes, I am spring cleaning in the fall and trying to catch up with friends and family. Since I have resigned myself to staying near my L.A. residing kids, I am considering projects to make me happier in the house I had planned to leave by 2020. Too bad I can’t move the Van Nuys airport and change the climate. On the bright side I have been traveling east frequently to visit family and friends.

I would love to have a Zoom happy hour so we could catch up. It has been a while!! What will your schedule allow? Mine is open especially in the afternoons and evenings.

Looking forward to catching up.

Janet

>

LikeLike

Thanks, Janet. Please contact me via email to set up a zoom.Lisa

LikeLike